When the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos affixed his signature on Proclamation No. 1081, the future of the country was left in a dire state of uncertainty. Apart from Marcos himself, no one knew what was coming.

But one thing was certain – the course of Philippine history would forever be changed.

Nearly four decades have passed since the infamous declaration of Martial Law. Those who were born after the years of military rule now only know of them through countless stories from survivors, educators, and textbooks that have been handed down to the younger generations.

The history of Martial Law is an ill-fated conglomeration of veiled truths and blatant lies. In pursuit of recollecting remnants from this grim past, the legitimacy of existing historical narratives is often held in question.

In hindsight, one must keep in mind that there is more to the events of those tumultuous years than what is commonly told.

Beneath the dictatorship’s tarnished facade, the multifaceted buildout under military rule carried motives untold and stories unheard.

Plotting the prelude

One of Marcos’ justifications for declaring Martial Law was the imminent threat of insurgency. During his second term in office, the emergence of the Communist Party of the Philippines – New People’s Army (CPP-NPA) was a key development.

In 1970, an ill-famed incident saw Lieutenant Victor Corpuz, an instructor of the Philippine Military Academy (PMA), spearhead the CPP-NPA’s attempt to raid the PMA’s armory of weapons and other equipment.

Furthermore, among the most significant landmark events during the Marcos presidency was the 1971 Constitutional Convention. To the surprise of many, the president endorsed the introduction of major amendments to the Constitution.

Subsequently, it was discovered that the underlying intent for concurring to the lobbied ratifications revolved on how the prospect of charter change offered Marcos an avenue to extend his tenure beyond the limits set by the 1935 Constitution.

At this time, talks of a coup d’état backed by key figures from the Liberal Party of the Philippines (LPP) such as Eleuterio “Terry” Adevoso and the United States of America were quickly spreading.

Plans to overthrow the government were deemed to have been initiated by his prominent critics like Sergio Osmeña Jr. and Fernando Lopez, Marcos’ vice president who lost the 1969 presidential elections.

Speculations began to rise, even with the international press, on how the sudden surge of unwarranted incidents comprises the potential prelude to Martial Law—one that was the brainchild of the president himself.

Marcos also reportedly wrote personal diary entries that listed down his plans to stage a series of disastrous events en route to the inevitable proclamation of Martial Law and the eventual extension of his presidency.

The diary entries intricately outlined how ouster plots from the opposition, orchestrated assassinations, mass terror threats, and a widespread killing spree could provide sufficient grounds and justifications to declare military rule and terminate the writ of habeas corpus as soon as possible.

By virtue of Proclamation No. 889, the writ of habeas corpus was suspended through another allegedly staged pretext—the 1971 LPP political rally bombing incident at the Plaza Miranda in Quiapo, Manila. Roughly 4,000 people attended the event in which hand grenades were thrown to the stage where several party members were situated.

Unfortunately, nine deaths and 95 injuries in total were recorded.

The public pointed at several suspected perpetrators and masterminds of the Plaza Miranda Bombing, including the CPP-NPA and Marcos himself.

Ultimately, the event that was considered to be the boiling point prior to Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law was the staged ambush of his Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile on September 22, 1972.

On that day, at around 9:00 pm, Enrile’s convoy was ambushed as it was exiting Camp Aguinaldo near the Wack-Wack subdivision area. Contrarily, a nearby resident named Oscar Lopez stated that another car arrived at the scene wherein a group of people riddled Enrile’s car with bullets to make it appear as if it was legitimately ambushed.

In his book “The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos,” former Marcos journalist Primitivo Mijares stressed that the orchestrated ambush was the final nail on the coffin to solidify the justifications for a nationwide martial law proclamation.

This event in full detail can be seen in Marcos’ diary entry at 9:55 pm on the same evening. According to him, “Sec. Juan Ponce Enrile was ambushed near Wack-Wack at about 8:00 pm tonight. It was a good thing he was riding in his security car as a protective measure […] This makes the martial law proclamation a necessity.”

In a monumental press conference on Feb. 23, 1986, Enrile made a huge revelation to the public—his “ambush” was faked.

Enrile also confirmed that the ambush was, indeed, motivated by Marcos’ intent to justify the proclamation of Martial Law.

Two days later?

The commemoration of Marcos’ declaration falls on September 21st. In reality, this is often a disputed claim.

On this day in 1972, Philippine democracy was still intact.

The late senator Benigno Aquino Jr. delivered his eventual final privilege speech in the Senate. Concurrently, the House of Representatives was still in session with their closing committee meetings.

Elsewhere, the Concerned Christians for Civil Liberties launched a protest at Plaza Miranda. An estimated 30,000 people from across various civic, religious, labor, and student groups participated with widespread media coverage to follow the latest developments.

By this time, Marcos had already finalized the details of Proclamation No. 1081 with the members of his Cabinet and staff, as explained in his diary. The declaration was already signed, but the Filipino people were yet to be made aware.

According to The Official Gazette, there are still several conflicting accounts to this day on the whereabouts of the actual proclamation and the exact date when Marcos put pen to paper on the said document.

Another dimension of the story eventually surfaced, explaining Marcos’ profound obsession with numerology and the number 7. This led to the formation of theories on his deliberate move to sign the declaration on a date divisible by 7, which in this case is the 21st of September.

In a tweet, former Supreme Court spokesperson and human rights lawyer Theodore Te states that it is vital to understand the difference between when Martial Law was signed and when it was formally declared.

Meanwhile, in a separate tweet, Filipino historian Kristoffer Pasion explains the chronological sequence of events on the buildup to Marcos’ proclamation.

Above all this, one thing was certain – the Philippines learned its fate from the man himself just two days later.

Dawn of democracy’s demise

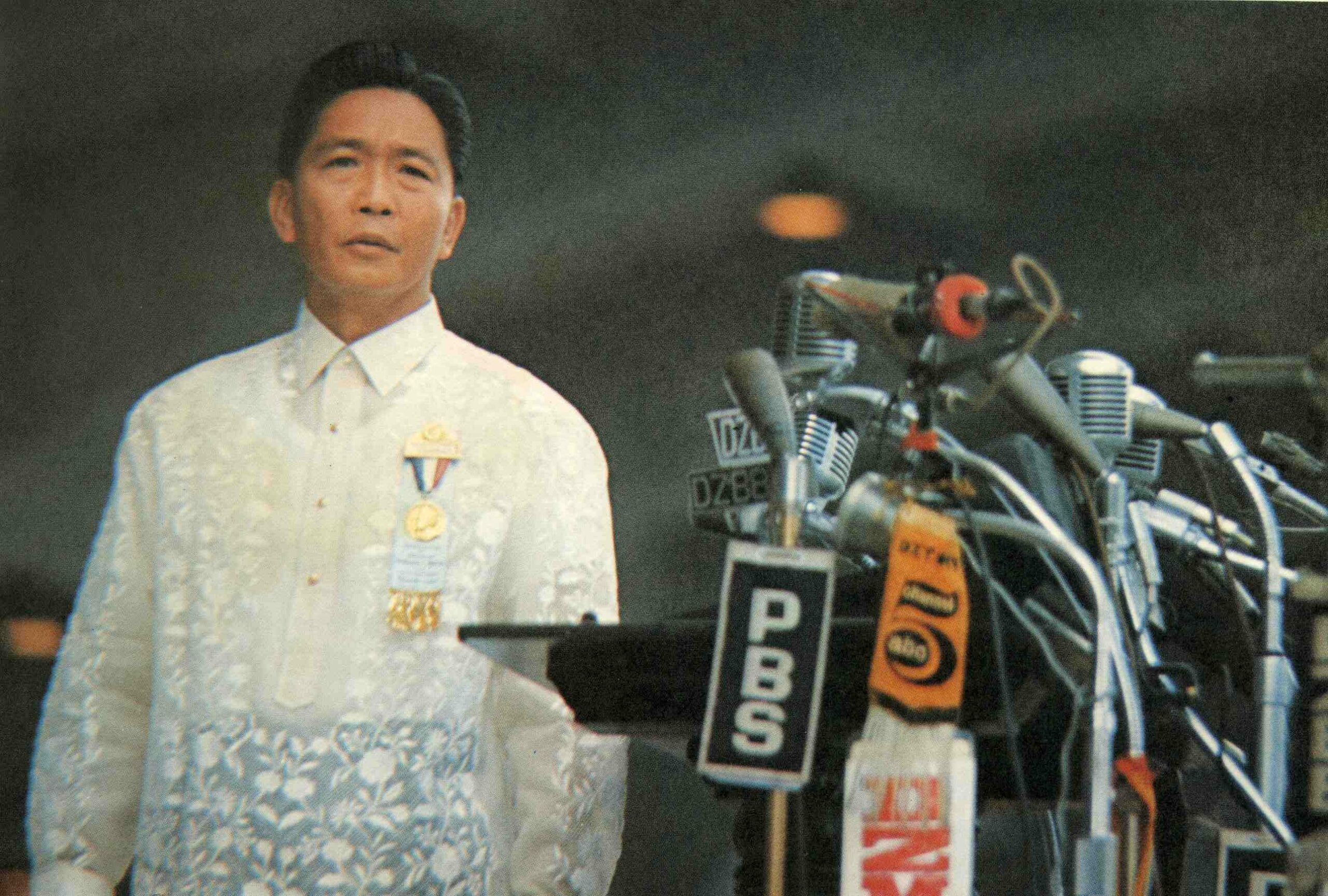

“By virtue of the powers vested in me by the Constitution as the President and commander in chief of the AFP, I hereby declare martial law.”

In what is considered to be the catalyzing moment that led to one of the darkest chapters in Philippine history, Marcos made his public television address to the Filipino people on Sept. 23, 1972, at exactly 7:15 pm.

Following the announcement, six orders and letters of instruction were enacted by the regime with immediate effect.

These involved the president’s assumption of all state powers, detainment of dissenting politicians and media personalities, shutdown of private media, takeover of public utilities, seizure of all privately-owned watercraft and aircraft machinery registered in the country, and implementation of immigration restrictions for all Filipino citizens.

Under military rule, approximately 60,000 personnel now comprised the country’s Army, Navy, Air Force, and Constabulary state forces.

Marcos’ hot pursuit of clamping down the media saw seven television stations, 93 publications, and 292 radio stations ceasing their operations nationwide.

With 12 security personnel killed and roughly 8,000 individual arrests made on the first day of Martial Law alone, 4 incumbent senators were held captive: Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., Jose “Pepe” Diokno, Ramon Mitra Jr., and Francisco “Soc” Rodrigo.

At present, amid the inevitable rampancy of misinformation and historical distortion, the Filipino people must not lose track of a vivid and accurate presentation of an ill-fated chapter of Philippine history.

While this inhumane dictatorship is long gone, there are those who would wish to whitewash its legacy and return those who profited from it to power. Defending the inviolable rights of each Filipino and exercising the right to suffrage in a few months’ time are among the vital keys to ensuring a future free from abusive and fascist leaderships.

As we commemorate Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law, our collective stance as a nation must remain firm and resolute, now more than ever.

Never forget, never again. DZUP